The draft EU Data Act applies in addition to the GDPR. It is not sufficiently aligned with the existing regulation.

On 9 November 2023, the European Parliament adopted the EU Data Act by a large majority, after having previously agreed it with the Council in an informal trilogue (text of the EU Data Act). The goal of the EU Data Act is to create a starting framework for data sharing in the European internal market. It therefore naturally clashes with the traditional understanding of data protection, which aims to improve data economy and avoid the dissemination of data. Does the EU Data Act solve these problems itself or does it just create contradictions and ambiguities?

Significant overlap between the EU Data Act and GDPR

The EU Data Act is intended to incentivise data sharing through numerous provisions.

Firstly, data holders (usually product manufacturers) must provide users with the data generated from using a purchased, leased or rented product. Secondly, data holders must provide the data directly to third parties at the user's request.

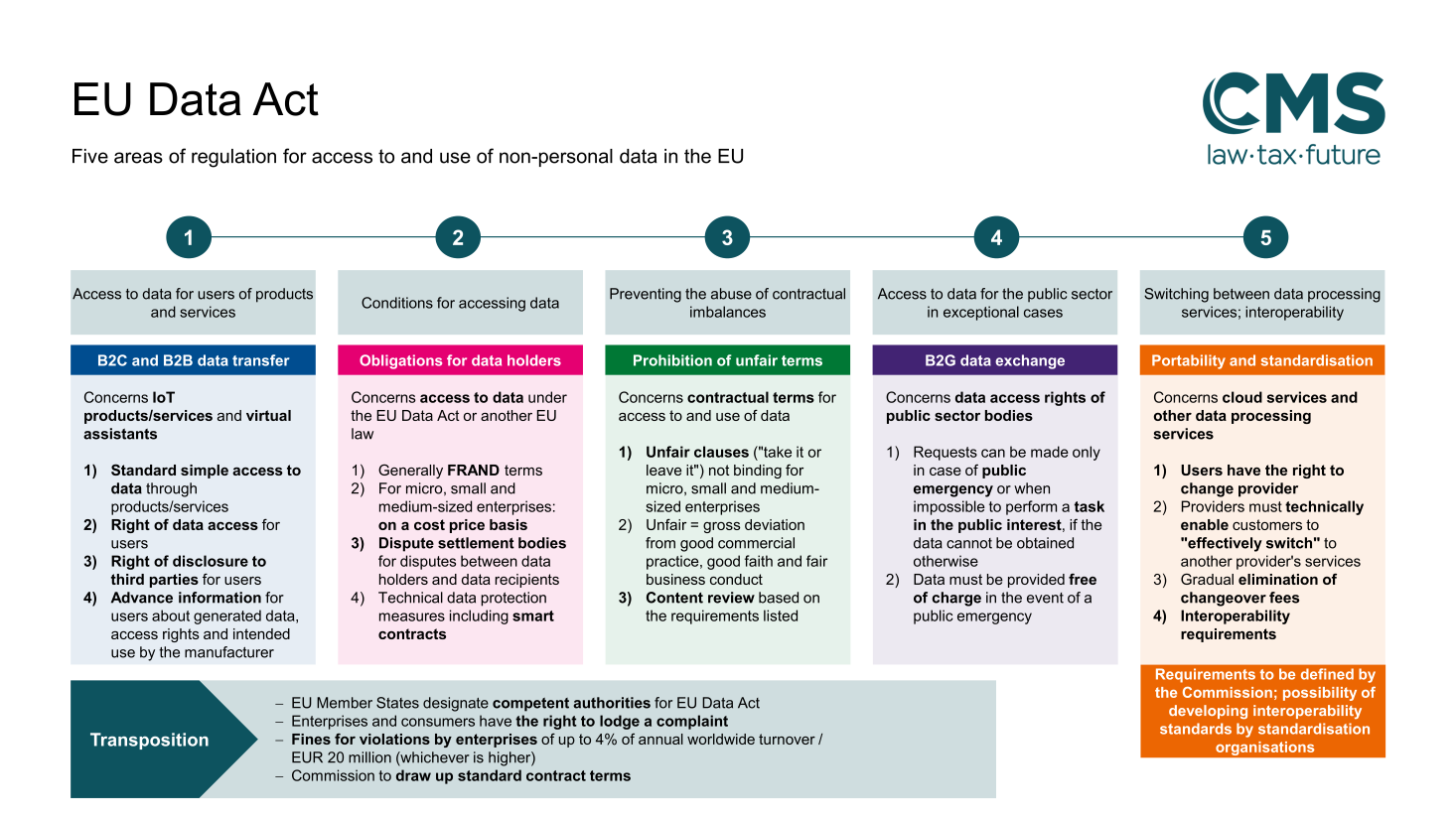

The EU Data Act safeguards these two rights of users with a whole package of measures, which are also intended to put data sharing on a solid footing based on other laws. Users must be informed about their rights to access and share data whenever they purchase or rent a product that generates data. The sharing of data between data holders and third parties is standardised by many other provisions, in particular through the data holder's obligations regarding data access, through a prohibition of unfair terms and through requirements when switching between data processing services:

The EU Data Act applies to data of any kind that users generate intentionally by using the product or as a by-product of using it (Article 2 No 1 EU Data Act). It also covers data generated by a service closely associated with the product (e.g. a virtual assistant on a smart speaker). However, the EU Data Act does not apply to purely digital services.

Even though the EU Data Act also covers non-personal data, most of the data generated by particular users are personal data. For example, the data generated by smart cars, IoT devices and other consumer goods can typically be attributed to an identifiable person, making them personal data. They are therefore subject to the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Pseudo-solution through a non-affection clause

The EU Data Act is "without prejudice" to the GDPR; the GDPR will take precedence over the EU Data Act (Article 1 (5), recital 7 sentence 5 EU Data Act).

The EU Data Act and GDPR are therefore supposed to be interpreted in such a way that they complement each other as much as possible and carefully balance each other out through mutual consideration. However, the EU Data Act provides only a few hints as to how the two regulatory regimes can be aligned. This problem-avoidance strategy creates legal uncertainty.

The following three sections discuss the relationship between the EU Data Act and the GDPR for three especially practical potential areas of conflict: the users' right to access data, the users' right to share data with third parties and the obligation to provide information to users.

Users' right to access data

A key right of users in the EU Data Act is the right to access data. Data holders must provide users at their request with the data generated by products (Article 4 EU Data Act).

The users' right to access data complements their right to access personal data under Article 15 GDPR while also going beyond it. Firstly, it also covers non-personal data, even though as mentioned above, most of the product-generated data are personal data. Secondly, it covers data access in real time, in as far as this is possible. Thirdly, it can be exercised by any user, not just the person the personal data relates to (the so-called data subject). The user is the natural person or legal entity which has rented or purchased the product (including any company that purchases data-generating products).

But do data holders even have legal grounds under Article 6 GDPR to grant users access to data?

If the data subject is a user (e.g. in B2C transactions), this does not appear to be a problem. In that case, data holders can rely on the legal grounds of "compliance with a legal obligation" (Article 6 (1) (c) GDPR, Article 4 EU Data Act). It is unclear whether this applies to the personal data of family members (e.g. registered users of a smart home refrigerator). Data holders may be able to disclose personal data of family members on the grounds of the so-called household exemption in the GDPR (Article 2 (2) (b) GDPR), though the EU Data Act does not address this issue.

It is also unclear whether data holders may grant access to data if the users themselves are legal entities (e.g. an employer that has purchased a smart company car and is therefore its user). The EU Data Act states that valid legal grounds pursuant to Article 6 GDPR are required in this case (Article 4 (12) EU Data Act). In addition to consent, such legal grounds will primarily be the performance of the contract in accordance with Article 6 (1) (b) GDPR (recital 34 sentence 8 Data Act). In order to use the legal grounds of legitimate interests, users must weigh their legitimate interests against the interests of the data subjects. Unfortunately, the EU Data Act does not specify any admissible case groups for this task of weighing interests, which depends heavily on the individual case, nor does it provide any other guidance.

Users' right to share data with third parties

The second key right of users is the right to share data (Article 5 EU Data Act). According to this right, data holders must also grant third parties access to data if users request this or if authorise third parties to do so. This complements the right to data portability under Article 20 GDPR, which is expressly not superseded (Article 1 (5) sentence 3, recital 31 sentence 15 EU Data Act).

However, in contrast with the GDPR, the EU Data Act provides for the sharing of data directly with third parties, not just providing them to the data subject in a machine-readable format. It also applies to non-personal product-generated data (even though product-generated data is usually also personal data). The right to data portability is currently largely irrelevant, as interoperable formats are not widely used. The EU Data Act therefore devotes an entire chapter to interoperability (Articles 33 to 36 EU Data Act). The right to data portability is further limited by the fact that third parties (not users) must pay appropriate compensation (Article 9 EU Data Act).

If users are legal entities (e.g. employers in the case of smart company cars), legal grounds pursuant to Article 6 GDPR are required in the same way as for the right to access data (Article 4 (12) EU Data Act). Once again, there is legal uncertainty on account of the unclear standards.

Obligations to provide information

In order to safeguard both rights, users must be provided with certain information before concluding a purchase or rental agreement. This information includes, in particular, the type and scope of product-generated data, how users can access these data and for what purposes data holders will use the product-generated data (Article 3 (2) EU Data Act).

Article 3 EU Data Act should apply in addition to the obligations to provide information under Article 13, 14 GDPR (recital 24 sentence 7 EU Data Act).

Naturally, the information to be provided overlaps substantially with the information to be provided under Articles 13, 14 GDPR. However, it also includes additional information (e.g. whether products generate data continuously and whether users' rights are to be exercised). In addition, it is intended for users who, as previously mentioned, are not necessarily the same persons as the data subjects.

The lack of coordination between the two information catalogues could lead to consumers being even more overwhelmed by the large amount of information.

In future, companies will probably provide an additional document with the mandatory information under the Data Act. Alternatively, it could make sense to integrate the information into the general privacy notice in order to avoid duplication.

Hope for harmonisation in the application of the law

In the interests of legal certainty, hopefully the courts will in time succeed in reaching a nuanced alignment of the individual rights and obligations of the EU Data Act with the GDPR. The EU Data Act could then better achieve its objective of free movement of data in the European internal market, which it also shares with the GDPR (Article 1 (3) GDPR). Until then, however, the relationship between the GDPR and the EU Data Act will be the subject of much debate.

Social Media cookies collect information about you sharing information from our website via social media tools, or analytics to understand your browsing between social media tools or our Social Media campaigns and our own websites. We do this to optimise the mix of channels to provide you with our content. Details concerning the tools in use are in our privacy policy.