Introduction

A recent judgment from the UK Patents Court serves as a helpful reminder that clarity and consistency of visual representations are essential, when filing for design registrations.

In the case of Safestand Ltd v Weston Homes PLC & Ors [2023] EWHC 3250 (Pat), the court dealt with allegations of patent infringement and the validity of registered designs related to builders' trestles.

The claimant, Safestand, argued that Weston Homes infringed three of its patents and three of its re-registered EU designs (“RRDs”, previously known as Community Registered Designs). Weston Homes countered by challenging the validity of two of the patents for lack of inventive step, and all three RRDs for lack of unity/clarity and individual character over the cited prior art.

The judge, HHJ Hacon, held that the three patents were valid and had been infringed, but that the three RRDs relating to the trestles were not valid as their visual representations showed multiple design variations. Accordingly, there could be no registered design infringement.

The RRDs

The RRDs – referred to as RRD 0001, 0004 and 0005 – were all titled “Trestles for building industry”. Builders’ trestles are a form of metal scaffolding used to support platforms for construction workers to stand on, in order to gain access to points of buildings or sites. Each of the RRDs comprised a series of images featuring the trestles in various states of construction. When assessing the validity of the RRDs, the court considered how the representations of the designs might be interpreted and whether or not the design claimed was clearly identifiable.

Clarity of interpretation

When filing for design registration, consideration must be given to the representation of the design and how it may be interpreted. In particular, as summarised in recent case law, consideration will be given to the following:

- Where the image is a photograph of a product, the design claimed consists of the features - the lines, contours, colours, shape, texture, materials and/or ornamentation - all as shown in the photograph.

- A design must be interpreted objectively; the subjective circumstances of the proprietor of the design, and, by extension, the intention of the designer in creating the design, are not relevant.

- Products manufactured by the owner of the design, which are said to be protected by the registered design, are also irrelevant to the interpretation of images – save that, where it is accepted that a manufactured product corresponds to the design as shown on the register, it is legitimate for a court to take physical samples of that product into account when carrying out its assessment.

- Objective interpretation of a design is a matter for the court and not for the court viewing the design through the eyes of the ‘informed user’. This is because the ‘informed user’ is unlikely to be aware of what dotted lines, grayscale, etc. are intended to convey in the representation.

Single article or different embodiments?

Weston Homes argued that Safestand’s RRDs lacked clarity because the representations featured multiple coloured parts and it was not clear which of the parts were connected with one another, or how they were connected. An assessment was therefore required as to whether the representations were of a single design, or several alternative embodiments of the same design.

While a design for a single article that comprises multiple parts may be registered as a ‘complex design’ it must be a single article whose parts are mechanically connected – meaning, the representation submitted will relate to the appearance of one and the same product, or of its parts. Alternatively, protection can be claimed for a set of articles, which make up one single product, but which are altogether linked by aesthetic and functional complementarity. For a set of articles, the representation may feature all articles in combination together.

By way of example, design protection may be sought for a chess board with all of its playing pieces. This would be considered a set of articles and not a ‘complex product’ because the articles are not mechanically connected.

However, the design will not be deemed a single article if the representations submitted are of different embodiments of the same design concept, and no representation of the design as a whole is submitted. Instead, the different embodiments would be considered different designs; a single application cannot be filed to protect alternative versions of one design even it has an overall “theme”. All ‘views’ of the design must represent the same design object and the totality of the shape of the claimed design must be clear when looking at the views collectively.

The court’s decision

The court concluded that the three RRDs sought protection for a builders’ trestle in several alternative embodiments, rather than a single design. As a result, none were found to be validly registered.

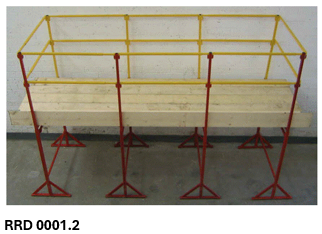

In consideration of RRD 0001, it was found that image 0001.2 depicted the trestle in its complete form, with the other representations depicting parts. The representations are reproduced in full below.

As a result of several ambiguities, including the following, it was held that the representations depicted various different embodiments of the design:

- Neither images 0001.6 or 0001.7 (of the kickboard brackets) appeared in the representation of the complete form (at 0001.2). Kickboard brackets may therefore be optional and, even if they are not, may be either red or green.

- Image 0001.3 is of a ladder holder extension. This appears in yellow in 0001.1 and 0001.3 but not in 0001.2. By its nature, it implies that there are multiple embodiments of the design when the extension is used.

- Anti-flip brackets may be either red or green (featured in red in 0001.1 and green in 0001.5) and may also be optional.

The ambiguities the judge found in respect of RRD 0001 were also found to apply to RRD 0004 and 0005. It was further noted that, had the judge not been able to reach a clear conclusion that the RRDs were of several embodiments, then the RRDs would have been invalid for a lack of clarity: on either ground, the RRDs would not have been validly registered.

Commentary

This case serves as a useful reminder for those seeking design protection, that the representations of the design must be sufficiently clear and capable of being objectively interpreted by the court. Further, it is necessary to ensure that the representations of the design can be reconciled as depicting a single design, and not different variations, embodiments, or configurations of an article, as this would require multiple applications.

Additionally, the case underscores the important intersection between patent and design right protection, and the scope of protection available under each right. While Safestand’s RRDs were held to be invalid, it was found that their patents for the same builders’ trestles were valid and had been infringed by Weston Homes. In some cases, “double protection” by way of concurrent patent and design filings can offer a valuable back-up option where one right is deemed invalid or infringement cannot be established. As patents and designs protect different aspects of a product (the former giving protection to an inventive technical solution, and the latter protecting its appearance), a claim based on one right may succeed even where the other does not.

That being said, businesses should be aware of the risk of these two forms of IP potentially cutting across each other. The recent judgment in Chiaro Technology v Mayborn [2023] EWHC 2417 (Pat) (reported by Law Now here) confirmed the principle set out in a string of previous cases that the existence of a patent for the claimant’s product can serve as ‘objective evidence’ that features of shape in a registered design for the same product are “solely dictated by technical function”, therefore potentially compromising the validity and/or scope of the registered design. In the Safestand case, the RRDs were declared invalid for a reason unrelated to the claimant’s patents – but nevertheless, businesses should think carefully about the possible overlap in technical function and appearance in choosing their IP protection strategy.

Social Media cookies collect information about you sharing information from our website via social media tools, or analytics to understand your browsing between social media tools or our Social Media campaigns and our own websites. We do this to optimise the mix of channels to provide you with our content. Details concerning the tools in use are in our privacy policy.